To speak of Roman Haubenstock-Ramati is to enter into a large semiotic and emotional debate: many theorists, critics and musicologists have downplayed the innovative power of the Polish-born composer, considering that its main feature, namely the graphical score, is simply to be evaluated on the basis of visual art (see the reasons articulated by authors like Rossiter or Monelle): to a good approximation and in too-concrete terms, the wonderful intuition that Haubenstock-Ramati shared at the time with American composers (Cage, Feldman, Brown, etc.) and a few other European composers (Ligeti, Stockhausen, the forgotten Logothetis, Xenakis, etc.) comes to terms with the current of thought that one cannot find, given the complexity of the design, the connection between the graphic score and the sound event, also stemming from the fact that Haubenstock-Ramati in his theoretical writings said that the musical result was dominated by the novelty and the power of the graphic writing. Today, graphic notation is an essential tool for approaching musical performance, a practice made continually desirable by composers who have identified a sparkling character of freedom and creativity and a sincere removal of the stringent rules of the classical score: therefore the historical position of Haubenstock-Ramati is found within indeterminacy and free improvisation, and the score operates like an instruction manual for the use of a household appliance, in which the user find associations for the clear functioning; not only must the interpreter have knowledge of these associations in the score, but he also must have the intellectual talent to find in the graphic forms a kind of transcendent sound, which can be customized: the composer distributes the access codes, the performer finds his answers in the (more or less) wide space opened by the composer.

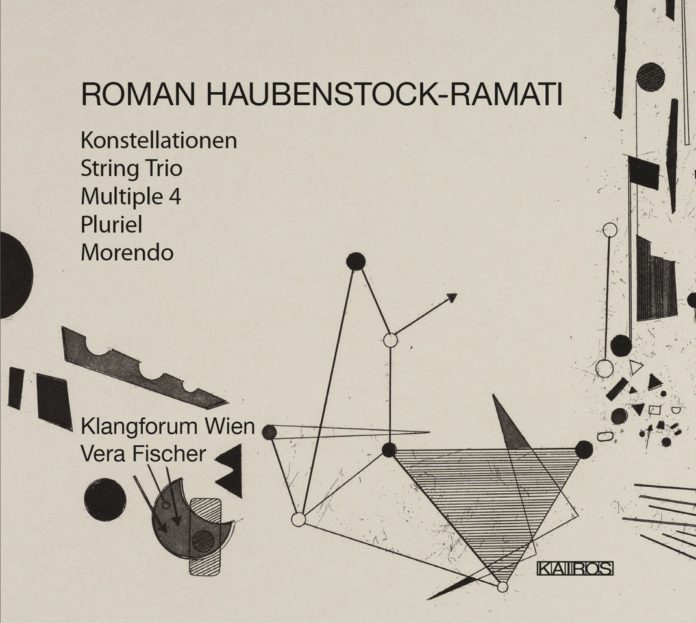

The members of Klangforum Wien are the main protagonists of this Kairos compilation dedicated to Haubenstock-Ramati: with an excellent recording the ensemble quickly traces the compositional phases experienced by the composer, early in the shadow of Webern theories (here is reprised the String Trio # 1 of ’48), then with the first substantial deviations from the traditional pentagram (Multiple 4, ’65) and then by taking charge of the notational system that will make him famous (here we are provided with 3 versions of Konstellationen), until finally when Haubenstock-Ramati regained his feet a little (Pluriel is his string quartet). Quite apart from the semiotic characters that music can provide, the interpretations of the Klangforum components are declarations of love for the sound and its mood states: it is an atonality of fine workmanship, where the study of and attitude toward musical structures are condensed into a perfect interpretation (I would point out the splendid impressions received from listening to Krassimir Sterev’s accordion and Vera Fischer on flute in Konstellationen; impressive as well is the duet between Markus Deuter (oboe) and Christoph Walder (horn) in Multiple 4.

These versions do not make one regret at all the evolutions of scores heard in Blume’s or Furrer’s conducting, in compositions such as Decisions or Mobile for Shakespeare, however, pointing out that there is a gulf between scores as Multiple 4 and Konstellationen, in terms of lightness and “frail” sounds, compared to the complex configurations, art design of Konstellationen, as identified in the liner notes by Stefan Dress.

The collection does not offer insights on the side of orchestra or piano, but contains Morendo, a composition of ’91, atypically addressed to electronics, which included a part for bass flute that was never written because of the composer’s death: Bernhard Lang is responsible for its reconstruction (he allocates the performance to Fischer), through the part written for tape, suitably modified with software and Calder’s capacity for variation, one of the stylistic models for Haubenstock-Ramati’s musical symbiosis.

____________________________________________________________________________IT

Parlare di Roman Haubenstock-Ramati significa accendere un profondo dibattito semiotico ed emotivo: ancora oggi non sono in pochi coloro che hanno smorzato la carica innovativa del compositore di origine polacca e che ritengono che la principale caratteristica profusa, ossia la partitura grafica, sia semplicemente da valutare sulla base dell’arte visuale (vedi con ragionamenti articolati autori come Rossiter o Monelle): con buona approssimazione e troppa concretezza, quella splendida intuizione che Haubenstock-Ramati condivise all’epoca con i compositori americani (Cage, Feldman, Brown, etc.) ed altri sparuti europei (Ligeti, Stockhausen, l’oscurato Logothetis, Xenakis, etc.) fa i conti con quella corrente di pensiero che non è capace di trovare, di fronte alla complessità del disegno, il collegamento tra partitura grafica e manifestazione sonora, deviata anche dal fatto che Haubenstock-Ramati affermò nei suoi scritti teorici che il risultato musicale conta poco dinanzi alla novità e alla potenza determinata dalla scrittura grafica. Sta di fatto che la notazione grafica oggi è uno strumento di approccio all’esecuzione musicale per molti essenziale, una pratica resa continuamente auspicabile dai compositori che hanno individuato uno scintillante carattere di creatività e libertà ed un abbattimento sincero delle regole stringenti della partitura classica: la posizione storica rivestita da Haubenstock-Ramati sta perciò dentro l’aleatorietà e l’improvvisazione libera, che opera come un libretto di istruzioni per l’uso di un elettrodomestico in cui si richiede all’utilizzatore di rendere evidenti le associazioni per il suo buon funzionamento; all’interprete spetta di avere non solo una conoscenza di queste associazioni nella partitura, ma anche avere una predisposizione intellettiva nel trovare in quelle forme grafiche una sorta di trascendenza sonora, che può essere personalizzata: il compositore distribuisce i codici di accesso, l’esecutore trova le sue risposte nel (più o meno) ampio spazio seminato dal compositore.

I membri del Klangforum Wien sono i principali protagonisti di questa compilazione Kairos dedicata a Haubenstock-Ramati: con una presa d’ascolto eccellente l’ensemble ripercorre velocemente le fasi compositive vissute dal compositore prima all’ombra delle teorie Weberniane (qui viene ripreso lo String Trio n.1 del ’48), poi con le prime sostanziali deviazioni dal pentagramma tradizionale (Multiple 4 del ’65) e con la presa in carico del sistema notazionale che lo renderà famoso (qui vengono effettuate 3 versioni di Konstellationen), fino all’ultimo periodo in cui Haubenstock-Ramati tornò un pò sui suoi passi (Pluriel è il suo string quartet). Anche prescindendo dai caratteri semiotici che la musica può fornire, le interpretazioni dei componenti del Klangforum risucchiano l’amore per il suono e per i suoi stati umorali: è atonalità di pregevole fattura, dove lo studio e l’attitudine ad una sana interpretazione si condensa nelle strutture musicali (rimarcherei le splendide impressioni ricevute dall’ascolto della fisarmonica di Krassimir Sterev e Vera Fischer al flauto nelle Konstellationen, così come imponente è il duetto tra Markus Deuter (oboe) e Christoph Walder (corno) in Multiple 4. Queste versioni non fanno rimpiangere minimamente le evoluzioni di partiture ascoltate nelle conduzioni di Blume o Furrer in composizioni come Decisions o Mobile for Shakespeare, evidenziando comunque che tra partiture come Multiple 4 e Konstellationen ci passa un abisso in termini di leggerezza e “fragilità” dei suoni della prima rispetto alle configurazioni complesse, art design della seconda, così come individuate nelle note interne da Stefan Dress.

La raccolta non offre spunti sul versante composizione per orchestra o per piano ma contiene Morendo, una composizione del ’91, atipicamente rivolta all’ausilio dell’elettronica, che prevedeva una parte di flauto basso che non fu mai scritta a causa del decesso dell’autore: è Bernhard Lang che si occupa di ricostruirla (destinando l’esecuzione alla Fischer), ricavandola dalla parte scritta su nastro, opportunamente modificata con software e capacità di variazione alla Calder, uno dei modelli stilistici in simbiosi musicale di Haubenstock-Ramati.